Many of our earliest portrayals of history and introductions to history--the events that we tell ourselves have happened in the past--have never concretely happened. I do not mean to say that the events of the Gulf War did not take place (as some might contest, though this--to be sure--is more of a statement than a denial), or that some egregious historical turning point never maturated; rather, I mean to articulate the stark reality of elementary human history--we learn myths first. Our mythologies, whether stories of Arachne or of Hercules, are our first and most solid histories. The narratives of World War II, the stories of the USSR Gulags, the poems of the abolitionist movement--these stories (the real stories) are auxiliary to the mythology we learn first. Should we, then, resolve this to be a crisis of pedagogy? On the contrary, this is--perhaps--the way it should be. Myth holds the important piece in the human narrative, the only continual piece.

What role, then, does myth concretely play? The human soul, truly, desires something more (or less if one is to analyze the situation more acutely) than the real can offer. Myth is immune to questions of taxonomy, questions of dates, and issues of interpretation. All of this arises from the realization that myth transcends history and its limitations. The problem with reality and the facts, history & narrative, diaries & journals is one of emphasis--one of interpretation. Many historians who chose to narrow in one a sect of history--to create a discipline within the discipline of history--face problems. Historians of the first great war debate--to this day--about the events of this war, questions of interpretation, taxonomy, and dates often arise. Feminist historians tarry with the characterizations of pre-first wave feminism. Many historians of the Black Diaspora wrestle with questions of displacement. Queer history is not immune to this historical problem.

Queer histories often grapple with categorical taxonomy. Historians of the peculiar and the perverse are stuck asking questions about people, places, and events with answers that do not get at the modern lexicon of queer understanding. We risk, wholly, being anachronistic, being misunderstanding, being too redemptorist towards narratives we should be--ideally, though this is not always the case--hesitant to claim. The reality of Boston Marriages can perhaps be garnered in a positive light for the modern queer movement, though such a reality cannot be known. Similarly, we can--at the same time--reject or redeem those pederaists from Athens on the risk of abuse or amelioration. The questions of Oscar Wilde and Walt Whitman--while beautiful and intriguing (not to mention erotic)--might evade the precision of our modern language. History is precariously contingent on our faculties of language and time.

Do, then, our histories fail us? Perhaps. Quite acutely, perhaps.

There has been, in recent years, an influx of histories of pedagogical failure. Books, like "Lies My Teacher Told Me" have propagated the narrative that we have largely failed at advancing accurate histories. No such accounts of pedagogical failures exist on the side of mythology, precisely because no such failures can exist within mythology.

It seems then, that mythology cannot fail us--mythology can be historical, and mythology can portray real messages and accurate narratives of real that advance general motifs essential to experiences of the human soul and human consciousness.

When tasked with the question and qualms of queer history, iterated earlier, the answer again seems to lean towards a gracious advancement of our mythologies.

What are our queer myths? Do we have any?

In European mythologies (the white man's stories if you will) we receive no dearth of literature and oral tradition about same-sex relations between both men and women. Additionally, motifs of gender transformation are abundant. Many of the most revered of the Greek myths involves heroes experience victories in the bedroom and in the sky with elements of androgeny often at play.

Similarly, in Asian cultures, many tales of Dragon riders and mystics are laced with nuance and explicit reference to same-sex desire. Moreover, in early and reformist notions of Taoism, those with a willingness to explore, sexually, the body of all souls are seen and revered as wiser. Hinduism's most sacred and mystical gods are known to have avatars of both genders, endowing them with a sacred capacity for fluidity.

In West African tales, the creator of the Earth is of both Male and Female body at the same time. Other traditional South African narratives tell of celestial beings who engage in a sexual euphoria of a sacred nature with other celestial beings of similar gender-referenced bodies. Egyptian culture has no lack of queer influence deep within its many mythologies.

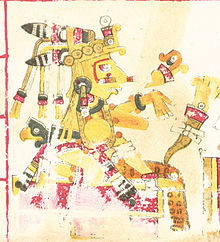

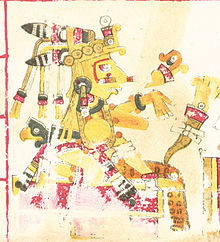

The Mayan God, Chin, is said to have gifted certain Mayans with the capacity to experience 'deeper pleasure' by engaging in acts of sodomy with other men. Similarly, the Tonsured Maize God was portrayed as being third gendered.

Native American notions of spirituality and gender are well known and prominent.

Our histories are limited and constricted by notions of language and consciousness, facts, and understanding. Our histories, queer or not, may fail us. Our Myths never do.

Comments

Post a Comment